Main Page > 2009 Gettin' Gettysburg Tour Intro >

The Boys landed into on a steamy hot East Coast day in Baltimore, with the temp way into the high 90's, so rather than be broiled and crabby from the sun, the boys decided to have boiled crabs at one of their old favourites, Obrycki's !!!

Oh My ! It's Obrycki's !!!

A gentleman named Charley Wedig opened a tavern at the original site in 1865 where soldiers quartered at the Union Camp of the 7th Maine Regiment at Patterson Park occasionally stopped in for a beer at the end of a long day. From 1866 until Prohibition in 1920, there were several different tavern owners, the most notable being George Gunther of the Gunther Brewing Company.

In 1944, Melvin Alexander purchased the property, and together with his brothers-in-law, Mitch, Joe, and Eddie Obrycki, ran a bar operation. Eventually, they decided to expand their business by serving food, featuring the delectable Maryland blue crab. At that point, Obrycki's became a restaurant.

Mike and Bone, getting rid of Crab's

The Boys order a big ole pitcher of beer and a boatload (pun intended) of crabcakes and steamy, dreamy peppered crabs. After two more rounds of crabs and beers, the Boys headed west to Gettysburg.

It could truly be said Mike and Bone had crabs !!!!!

Rich Kohr: A Wealth of Knowledge

Van, Mike's Son-In-Law might not be the most ambitious of human beings but certainly knew his Gettysburg Battlefield Guides when he hooked up Mike and Bone with Rich Kohr. Rich is a native of Lebanon, PA and a graduate of Lebanon Valley College. He has been a Licensed Battlefield Guide at Gettysburg National Military Park since 1995, and is a former President of the Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides. Rich has taught continuing education courses at Harrisburg Area Community College and has given lectures at numerous Civil War Round Tables. Rich proved to Mike and Bone that he was a walking encyclopedia of Civil War history!

He’s very enthusiastic and just a wealth of information! He took the boys on a chronological tour of the battlefield, stopping at key points of the various battles that took place over the course of three days to describe exactly what happened in that particular location. In many of the locations on the Battlefield, things that Bone had learned through his readings were provided a different context, so jumping into the Boys car off they went to "Get Gettysburg."

The First Shot of the Battle of Gettysburg

First things first, The best way to understand the Battle is to follow it day by day, almost hour by hour. With Rich took the boys to Chambersburg Pike whereon July 1, 1863, Lieutenant Marcellus Jones' service in the 8th Illinois Volunteer Cavalry had been undistinguished. In the rising humidity of that early morning, lead elements of the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac were poised to clash just west of the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg.

Jones commanded a forward outpost of cavalry videttes that spotted the Confederate advance along the road leading to Cashtown and Chambersburg. He carefully rested a borrowed cavalry carbine on a fence rail beside 31-year-old blacksmith Ephraim Wisler's home, took and held a breath and touched off a shot. It was about 7:30 a.m. Jones meant to give warning to Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's column and rapidly forming skirmish line. The mounted Southern officer on whom Jones drew a bead was still some 600 yards away. Little did Jones realize that his bullet would have far-reaching consequences, igniting a raging decades-long war of opinions among the veterans of Brig. Gen. John Buford's cavalry division over who fired that 'first shot.'

This first shot controversy is not unique — many arguments of both major and minor consequence arose from the Gettysburg battle, and dozens have spilled over from spats among veterans to quarrels among modern-day historians. What makes this controversy one of the more interesting, however, is that the dispute over whose trigger ignited the pivotal battle ultimately became a fight over the placement of and wording on the cavalry regiments' battlefield monuments.

Day One, coming down Chambersburg Pike

Interestingly, after the war, just as the fervor of regimental ornamentation on the Gettysburg battlefield began heating up in the 1880s, Marcellus Jones (promoted to captain by war's end) determined to memorialize his first shot for all time. Jones commissioned and paid for a small shaft marker to be carved of Naperville, Ill., granite, on which he had inscribed 'First Shot at Gettysburg — July 1st, 1863 — 7:30 AM — Fired by Capt. Jones with Sergt. Shafers carbine — Co. E, 8th Ills Cavalry.' In 1886 Jones traveled to Gettysburg with two regimental comrades to place his monument, among the earliest erected. Purchasing a tiny piece of ground from James Mickley, a former Union officer who then owned the Ephraim Wisler home, Jones' small party had the monument permanently installed just west of the home along the Cashtown Pike to mark the spot, where it still stands today. Its permanence was assured by sinking half its length into the ground.

Since it was erected on private ground, it was not subject to the regulations or approval of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA). Knowing nothing of Jones' monument, the monument committee of the 9th New York Cavalry met in Niagara Falls the following summer to begin the planning and design of a regimental monument at Gettysburg. One of its primary goals was to include inscriptions that prominently stated the regiment fired the first shot of battle on July 1, based on Alpheus Hodges' popular telling of his story. The front of the monument, in fact, is boldly inscribed 'Discovering the Enemy' and depicts a large relief sculpture of a 9th New York picket ready to fire the first shot. Staying true to Hodges' claim, the back of the monument reads, 'Picket on Chambersburg Road fired on at 5 am.' Marcellus Jones led a colorful life after the war and went to his grave in 1900 insisting on his place in the annals of the Battle of Gettysburg. At the 50th anniversary of the battle in 1913, 13 gray and aged veterans of the 8th Illinois Cavalry gathered around Jones' marker to pose for their final photograph as such a group at such a spot. At one end of the gathering waves a small American flag that someone placed on the fence rail where Jones had rested Levi Shafer's gun to fire. Standing erect and proud at the other end of the gathering is Shafer, holding hands with his wife, where, for one instant in time no longer than a muzzle blast, fate met history. With that story complete the Boys moved on.

Mike and Bone at the Grand Rapid Monument in the Peach Orchard

Rich, Mike and Bone moved on to the Peach Orchard where Day 2 started on July 2, 1863, most of both armies were on the field of battle. On Seminary Ridge were Longstreet's Corps making up the Confederate right and Hill's Corps to the left, extending north to meet Ewell's Corps, which held a semi-circular position on the south of town. The Union left, extending almost to the Round Tops (which were unoccupied), was Sickle's Corps III. It was here that Mike and Bone posed in front of the Grand Rapids Monument.

To his right was Hancock's II Corps and to his right was Howard's XI Corps, and covering the northern end and right flank of the Union line was I Corps. The Morning of July 2 passed relatively quietly, as Longstreet's Corps had not yet arrived in their jumping-off points for the days attack. The plan for July second involved Longstreet's Corps to attack Meade's left flank, which Lee believed sat on the Emmitsburg Road. At the same time, Ewell would attack from the north against Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill.

In the center, Hill would act as if attacking in order to keep the Union center from reinforcing against Ewell or Longstreet. Longstreet began his advance at about noon on July 2, moving first away from the battlefield in an attempt deceive the enemy, then to their attack positions.

As a result, it was several hours before the Corps was in position, and they had not even begun to fool the Union observers. Signalers on Round Top saw Longstreet's move, and in response, Sickles sent out the 3rd Maine and Berdan's Sharpshooters out who encountered Cadmus Wilcox's Brigade. A sharp fight ensued until the Union troops were forced to retire. When Sickles realized that the Confederates were massing in front of him, he moved his Corps from Cemetery Ridge to the Emmitsburg Road.

This move, however, caused gaps in the Federal line, which had to be filled as quickly as possible by units from around the line.

Finally, around four in the afternoon, Longstreet was in a position to launch the much-delayed attack. Major General Josh Bell Hood, one of Longstreet's division commanders, saw an opportunity to move even farther south, capture Little Round Top, and flank. Longstreet denied Hood's request, and the attack began as planned (although not as scheduled). Hood's Division began the attack, then McClaw's, and finally Anderson's.

Little Round Top

As the Confederates move toward Little Round Top, Brigadier General Gouverneur Warren (chief engineer) saw that the round tops were unoccupied, and ordered cannon fires on the advancing Confederates. However, the 15th Alabama, under Colonel William Oates, managed to take one side of the unoccupied Round Top. His efforts were for nothing, as he was ordered to withdraw. As he began the withdrawal, the 20th Maine, which had just arrived on Little Round Top, opened fire.

Chamberlin's View from Little Round Top

The 20th Maine was part of Colonel Strong Vincent's Brigade, which had taken the initiative, and occupied Little Round Top without orders. As Oates turned his attention to capturing Little Round Top, other regiments from Law's Brigade and Robertson's Brigade enter to fight. The right of the Union line on Little Round Top (16th Michigan) succumbed to the Confederate attack. Colonel Vincent rallied them, and the attack was beaten off, but not without a price--Vincent was mortally wounded. The Union Army may have lost Colonel Vincent, but they saved Little Round Top and prevented the Confederates from occupying the two round tops, from which they could have commanded much of the battlefield. In front of the 20th Maine, Oates's regiment continued to attack, and the 20th Maine, commanded by Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, continued to hold them off. Finally, as the 20th Maine was running out of ammunition, Chamberlain ordered a bayonet charge against the 15th Alabama . It succeeded; driving the 15th Alabama back to Round Top. The Confederates did not hold Round Top either, for that night, Colonel Joseph Fisher's Brigade and the 20th Maine, occupied the valuable piece of land. It was and still considered a brilliant military maneuver, especially from Chamberlin, whom was not a professional military soldier.

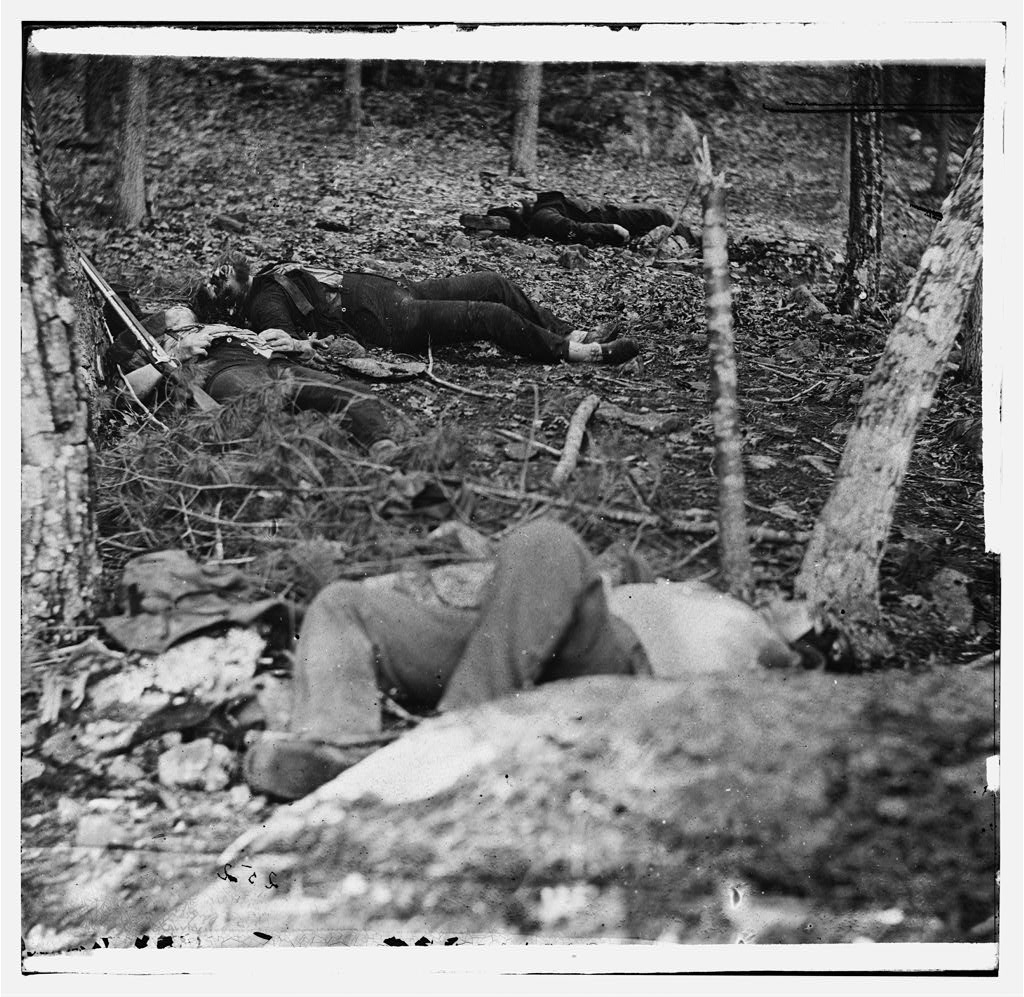

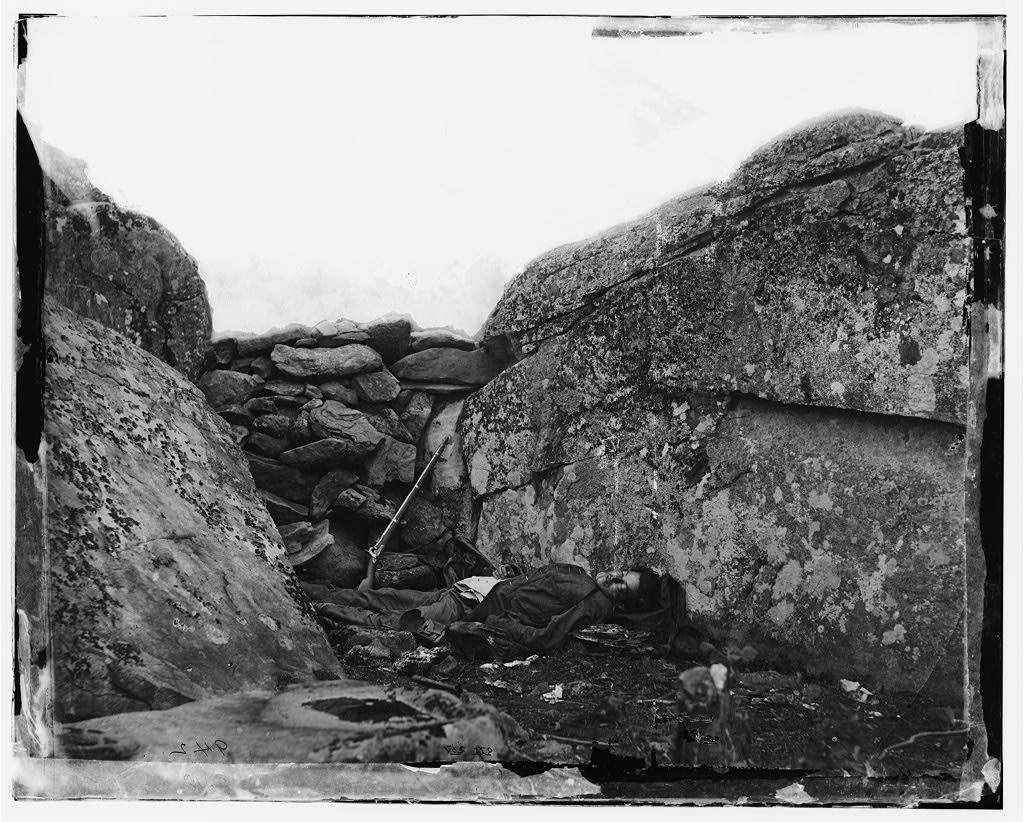

Horrors from the Battle on the Little Round Top

Mike and Bone walked down the Little Round Top and realized how small the field of battle was. Chamberlin's charge must have happened very fast, in order to surprise the Alabamian's unlike was is shown in the movie. This little factoid was one of Rich's little gems that he shared with Mike and Bone that day.

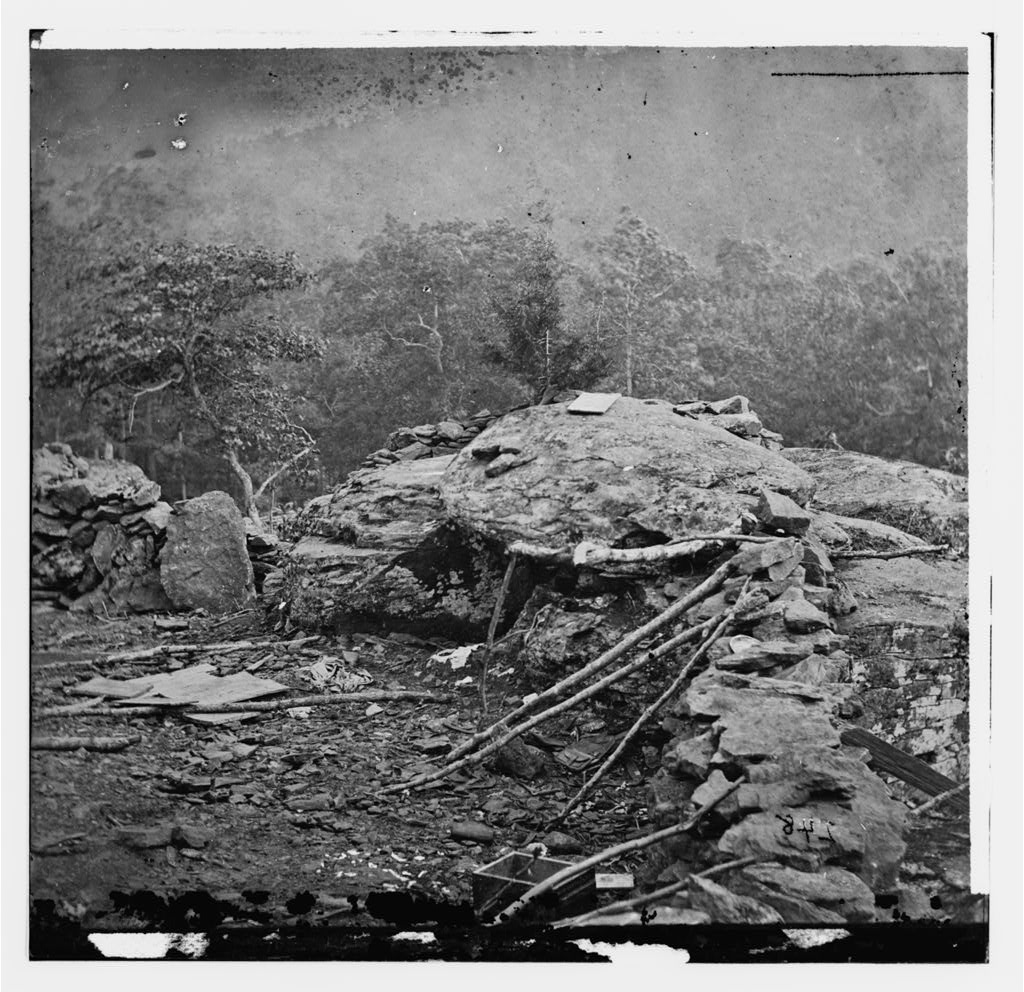

Devils Den: Before and Now

Fighting was fierce on Little Round Top, but also was it at other parts of the battlefield, especially at Devil's Den, The Wheatfield, and The Peach Orchard. The 1st Texas, 3rd Arkansas, and elements of Benning's Brigade took Devil's Den late in the day from Brigadier General Hobart Ward's brigade, and did not give it up until the retreat of the Army of Northern Virginia.

At the Wheatfield, Brigadier George Anderson's brigade attacked General de Trobriand's weakened brigade. However, reinforcements were provided by Jacob Sweitzer's and William Tilton's brigades. The Confederates were held at bay-but only for a short time. Brigadier Joseph Kershaw's Brigade , McClaws Division, entered the battle at the Wheatfield and helped push the Union line back. As the Union line wavered, Brigadier General John Caldwell's Division, II Corps, arrived to save the day. They charged into the Wheatfield, pushing the Confederates back and mortally wounding Brigadier General Paul Semmes. But the Confederates mounted another attack, inflicting heavy casualties on Caldwell's Division, which retired from the line. Finally Ayres's Division, V Corps, was thrown into the line, suffering heavy casualties. But the Union line held, and the Confederates were denied Little Round Top. As the brigades on the Confederate right advanced and pushed the Union troops back at Devil's Den and the Wheatfield, it was time for the next brigade in line, Barksdale Brigade, to move forward. As they advanced, the 57th and 114th Pennsylvania Regiments of Graham's Brigade, 1st Division, III Corps met them but were pushed back. They tried to regroup in the Peach Orchard, but the Confederate attack, supported by artillery, proved to be too much. The Pennsylvanians fell back with heavy casualties.

Late in the afternoon on July 2, Anderson's Division launched its attack against the Union line at the Emmitsburg Road. Wilcox's, Perry's and Wright's brigades advanced and pushed the Yankees back to Cemetery ridge but were stopped by a strong Union defense and lack of support from the brigades to their left. As the Confederates pulled back from Cemetery Ridge, the fighting on that part of the battlefield came to an end-but just beginning on another. On the northern end of the battlefield, Early launched an attack against Cemetery Hill and took it without much opposition. But the victory was short-lived. Union troops rallied and kicked the unsupported Confederates off the Hill. At Culp's Hill, Johnson attacked. He expelled some of the defenders from their position, but night rolled in, and the fighting ceased until the next day.

Day 3 Picketts Charge

Mike, Bone and Rich then drove to the Bloody Angle, the Union side of the epic part of Day 3, Pickett’s Charge.

Pickett's Charge was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee against Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's Union positions on Cemetery Ridge on July 3, 1863, the last day of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Its futility was predicted by the charge's commander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, and it was arguably an avoidable mistake from which the Southern war effort never fully recovered psychologically. The farthest point reached by the attack has been referred to as the high-water mark of the Confederacy, which is Pickett' Charge, which is pictured below.

The Bloody Angle at Picketts Charge

The charge is named after Maj. Gen. George Pickett, one of three Confederate generals who led the assault under Longstreet. After Confederate attacks on both Union flanks had failed the day and night before, Lee was determined to strike the Union center on the third day. On the night of July 2, General Meade correctly predicted at a council of war that Lee would try an attack on his lines in the center the following morning. The infantry assault was preceded by a massive artillery bombardment that was meant to soften up the Union defense and silence its artillery, but was largely ineffective. Approximately 12,500 men in nine infantry brigades advanced over open fields for three-quarters of a mile under heavy Union artillery and rifle fire. Although some Confederates were able to breach the low stone wall that shielded many of the Union defenders, they could not maintain their hold and were repulsed with over 50% casualties, a decisive defeat that ended the three-day battle and Lee's campaign into Pennsylvania. Years later, when asked why his charge at Gettysburg failed, General Pickett replied: "I've always thought the Yankees had something to do with it." Rich masterfully wrapped the Battle on Day 3 as as the sky grew dark on that hot summers day. It was an awesome tour leaving the Boys hungry and thirsty !!!

A Revolutionary Meal !

Mike and Bone met Van, Sarah and grandkids in town at old stone building built in the 1760's for Dinner. One of the reasons Gettysburg was the site of the Battle is that it is a cross roads between Baltimore, Washington, Philadelphia, and Lancaster. This Tavern dated back to those days and had great food and awesome craft beer. After a few hours Mike and Bone left early (for them) and retired early. They hadda get up early to chase the ghost of John Brown !