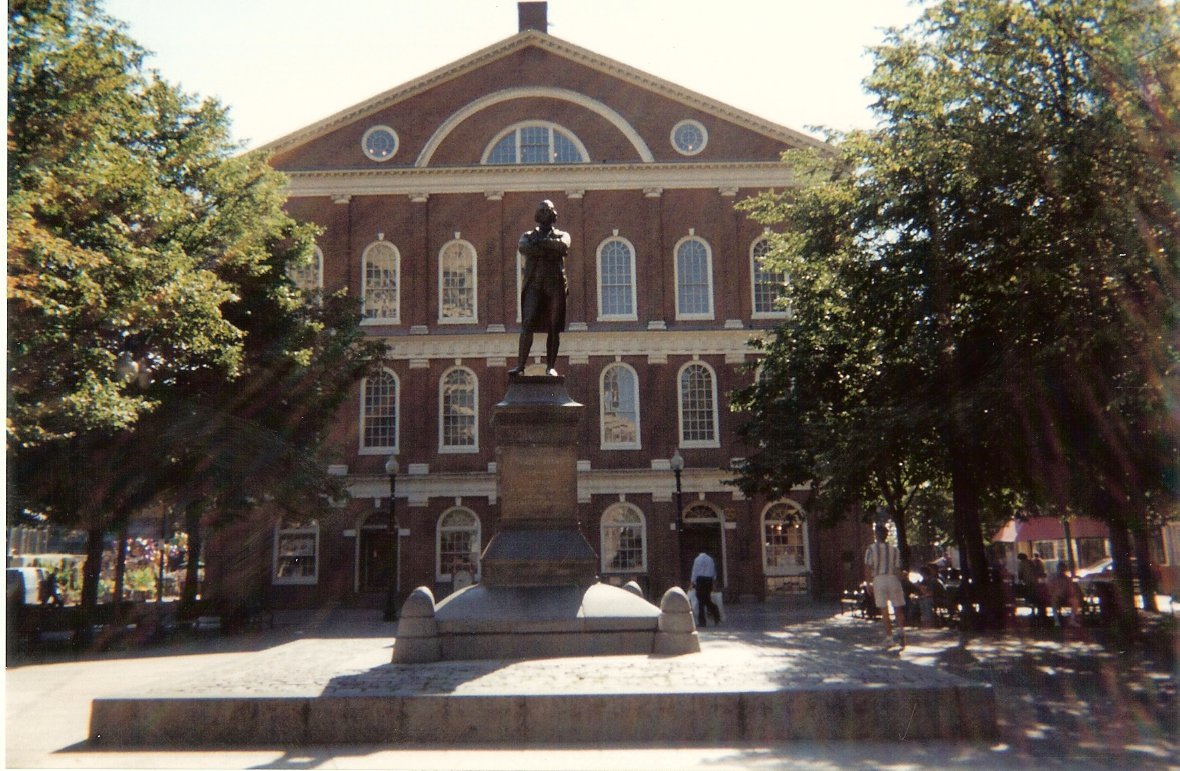

Day 3: Cheers to Boston !!!

Main Page > 1998 Oh My Cod !!! Its New England Tour ! >

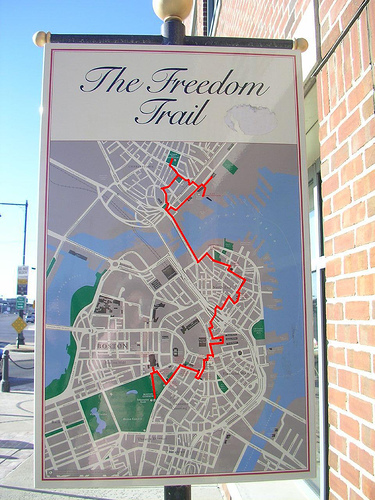

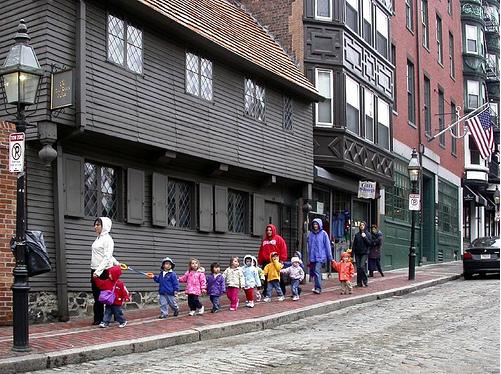

The next morning the Boys arose early, with tender and exfoliated rumps from ripping off the duct tape. Deciding they needed a little more heterosexual setting, they decide to head back up towards Bean-Town and check out the voluminous history of the "Cradle of the America Revolution." En route, the Boys decided to take a detour into Lexington and Concord, where the "Shot heard 'round the World" happened!

The Battle of Lexington Memorial

Mike and Bone made it to Lexington by 9:00AM with a full day planned.

Once at the National Park, there was a Park Ranger providing a historical walkthrough of the events in both Lexington and Concord.

The Original British Invasion did not have John, Ringo, and Geoge, just Paul (Revere!): Arriving on a holiday By April 1775 Boston was under British military control. On April 14, 1775, General Gage, commander of the British troops. received instructions from Secretary of State William Legge, the Earl of Dartmouth to disarm the rebels, who had supposedly hidden weapons in Concord, and to imprison the rebellion's leaders. Dartmouth gave Gage considerable discretion in his commands.

On the morning of April 16, Gage ordered a mounted patrol of about 50 men under the command of Major Mitchell of the 5th Regiment into the surrounding country to intercept messengers who might be out on horseback. This patrol behaved differently from patrols sent out from Boston in the past, staying out after dark and asking travelers about the location of Sam Adams and John Hancock. This had the unintended effect of alarming many residents and increasing their preparedness. The Lexington Militia in particular began to muster early that evening, hours before receiving any word from Boston.

Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith received orders from Gage on the afternoon of April 18 with instructions that he was not to read them until his troops were underway. They were to proceed from Boston "with utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord, where you will seize and destroy… all Military stores… But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants or hurt private property." Gage apparently used his discretion and did not issue written orders for the arrest of rebel leaders.

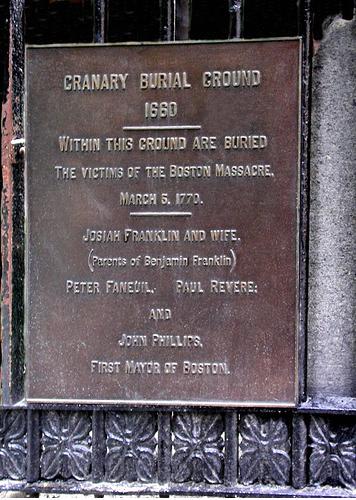

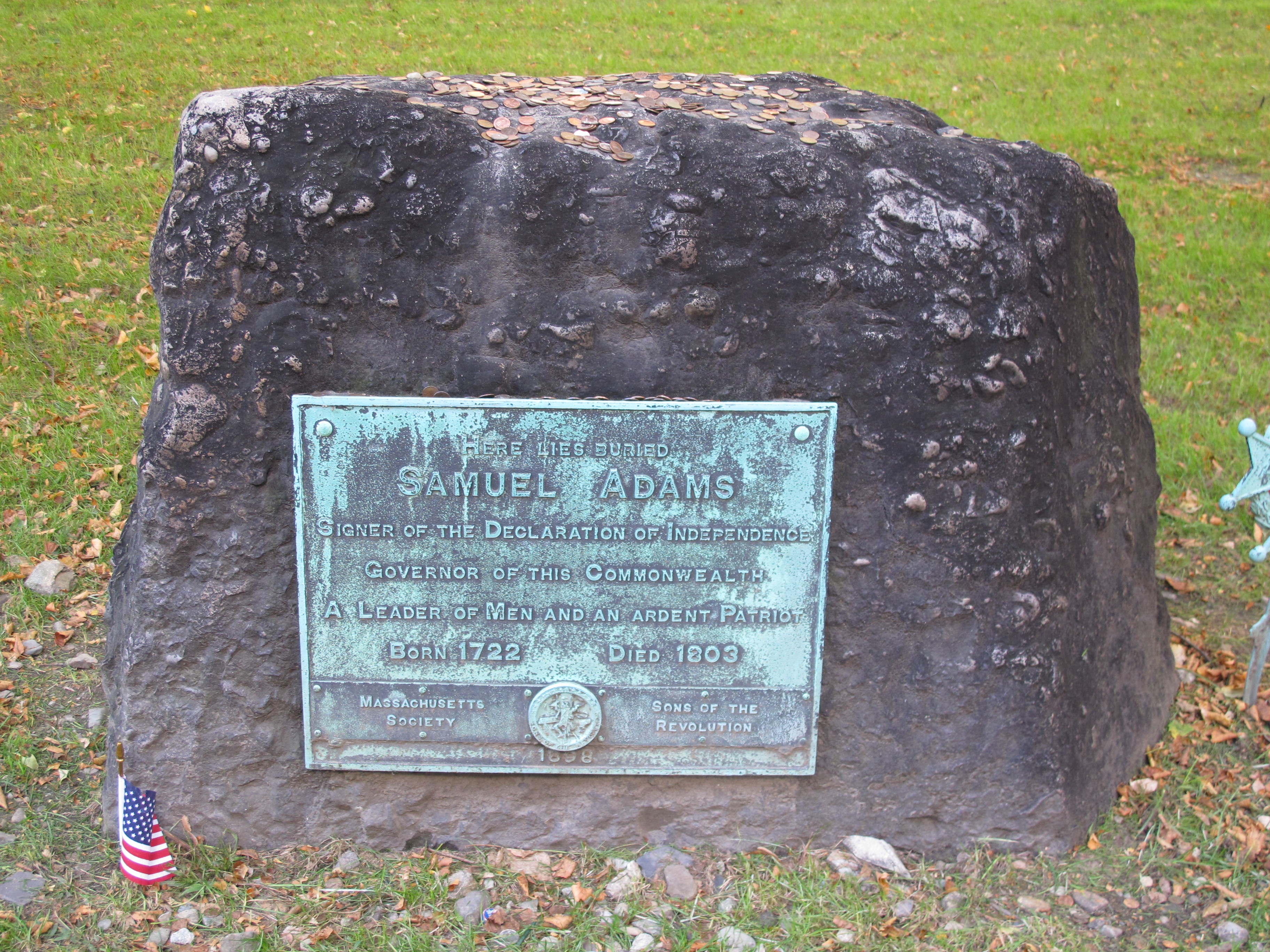

The rebellion's ringleaders with the exception of Paul Revere and Joseph Warren had all left Boston by April 8. They had received word of Dartmouth's secret instructions to General Gage from sources in London long before they had reached Gage himself. Samuel Adams and John Hancock had fled Boston to the Hancock-Clarke House, home of one of Hancock's relatives in Lexington where they thought they would be safe.

The Massachusetts Militia had indeed been gathering a stock of weapons, powder, and supplies at Concord, as well as an even greater amount much further west in Worcester, but word reached the Patriots that British officers had been observed examining the roads to Concord. On April 8, they instructed people of the town to remove the stores and distribute them among other towns nearby.

Between 9:00 and 10:00 PM on the night of April 18, 1775, Joseph Warren told William Dawes and Paul Revere that the King's troops were about to embark in boats from Boston bound for Cambridge and the road to Lexington and Concord. Warren's intelligence suggested that the most likely objectives of the British Army's movements later that night would be the capture of Samuel Adams and John Hancock. They worried less about the possibility of regulars marching to Concord. The supplies at Concord were safe, after all, but they thought their leaders in Lexington were unaware of the potential danger that night. Revere and Dawes were sent out to warn them and alert Patriots in nearby towns.

Dawes covered the southern land route by horseback across the Boston Neck and over the Great Bridge to Lexington. Revere first gave instructions to send a signal to Charlestown and then he traveled the northern water route. He crossed the Charles River by rowboat, slipping past the British warship HMS Somerset at anchor. Crossings were banned at that hour, but Revere safely landed in Charlestown and rode to Lexington, avoiding the British patrol and later warning almost every house along the route. The warned men and the Charlestown Patriots dispatched additional riders to the north.

After they arrived in Lexington, Revere, Dawes, Hancock, and Adams discussed the situation with the militia assembling there. They believed that the forces leaving the city were too large for the sole task of arresting two men and that Concord was the main target. The Lexington men dispatched riders in all directions and Revere and Dawes continued along the road to Concord. They met Samuel Prescott at about 1:00 a.m. In Lincoln, these three ran into a British patrol led by Major Mitchell of the 5th Regiment and only Prescott managed to warn Concord. Additional riders were sent out from Concord.

Revere and Dawes, as well as many other alarm riders, triggered a flexible system of "alarm and muster" that had been carefully developed months before, in reaction to the British colonists' impotent response to the Powder Alarm. "Alarm and muster" was an improved version of an old network of widespread notification and fast deployment of local militia forces in times of emergency. The colonists had periodically used this system all the way back to the early years of Indian wars in the colony, before it fell into disuse in the French & Indian War. In addition to other express riders delivering their message, bells, drums, alarm guns, bonfires and a trumpet were used for rapid communication from town to town, notifying the rebels in dozens of eastern Massachusetts villages that they should muster their militias because the regulars in numbers greater than 500 were leaving Boston. These early warnings played a crucial role in assembling a sufficient number of British colonial militia to inflict heavy damage on the British regular army later in the day. Samuel Adams and John Hancock were eventually moved to safety, first to what is now Burlington and later to Billerica.

Gage issued orders to have the entire 1st Brigade under arms, and ready to march at 4 a.m. The British regulars, around 700 strong, were led by Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith began their 17 mile march to Concord at about 2 a.m.

As they marched through Menotomy (modern Arlington), sounds of the colonial alarms throughout the countryside caused the few officers who were aware of their mission to realize that they had lost the element of surprise.