Main Page > 2012 Blues Brothers Tour >

Doin' the Delta !

The morning started out warm and humid on this fine Saturday in February with the Boys driving along the River through the heart of the Mississippi Delta for the 2 hour drive down to Vicksburg. The barley malt beverage depredations in the Shack Up Inn and Reds Blues bars the night before were not too bad, leaving the Boys not too worse for wear so they were able to enjoy the scenery of the Delta! The Mississippi Delta is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi which lies between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. The drive from Clarksdale to Vicksburg, Mike and Bone got through drove right through the heart of it.

The Delta has been called "The Most Southern Place on Earth" ("Southern" in the sense of "characteristic of its region, the American South"), because of its unique racial, cultural, and economic history. Technically the area is not a delta but part of an alluvial plain, created by regular flooding of the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers over thousands of years.

Because of all the flooding over the centuries of the Mississippi and Yazoo, this region is remarkably flat and contains some of the most fertile soil in the world. It is two hundred miles long and seventy miles across at its widest point. On the east, it is bounded by bluffs extending beyond the Yazoo River. Driving through it the Boys noticed the few houses and towns. Those they saw were in abject poverty. It is considered the poorest region of the US. After those coupla hours Mike and Bone landed in the lovely town of Vicksburg, site of arguable the most important battle of the Civil War!

"Ahh, can we speak to the Mayor?

The Battle of Vicksburg during the Civil War was fought at the same time as Gettysburg, and to Lincoln, was a more important victory. Arriving at the Vicksburg National Park, Mike and Bone asked if they had guides, similar to those they had at Gettysburg. A crotchetedy old woman behind the mis-named "Help" sign snarled to the couple in front of Mike and Bone, that all the guides were already taken for the day. When the Boys finally got up to the counter, they knew the answer but asked in their most sweetest southern sales drawl " Y'all know of any good guides there sweet heart ?!" With that little bit of sugar, the old lady brightened and said "Honey, I have just the guy for you all." Well, not only did she get the Boys a guide, she got the freakin' Mayor!!!

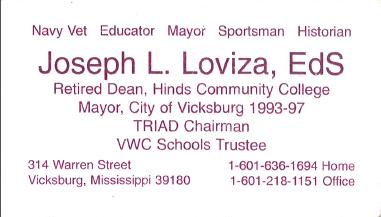

Joseph Loviza: Ex-Mayor, Educator, Southern Gentlemen from way back, and BS artist was awesome ! Mr. Joe's (as he wanted to be called) family actually fought for the Confederacy in the Battle of Vicksburg and turned out to be quite the character to discuss the battle. Here was the basics from "Mr. Joe. he started with two quotes:

“Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until the key is in our pocket,” – President Abraham Lincoln

“Vicksburg is the nail head that holds the South’s two halves together.” Jefferson Davis

Judging from the above quotes, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis both knew the extreme importance of the city of Vicksburg. At the beginning of the Civil War in particular Louisiana and Mississippi — the Mississippi River was closed to unfettered navigation, which threatened to strangle Northern commercial interests. This caused Lincoln to gather his civil and military leaders to discuss a strategy for opening the Mississippi River. Examining a map of the nation, Lincoln made a wide sweeping gesture with his hand then placed his finger on the map and said, "See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket." It was the Lincoln's contention that, "We can take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can defy us from Vicksburg. It means hog and hominy without limit, fresh troops from all the states of the far South, and a cotton country where they can raise the staple without interference." Lincoln assured his listeners that, "I am acquainted with that region and know what I am talking about, and, as valuable as New Orleans will be to us, Vicksburg will be more so."

These powerful statements from the Lincoln were no exaggeration. Confederate cannon mounted along the bluffs commanding the Mississippi River at Vicksburg were trained on the river, denying that important avenue of commerce to Northern shipping. It is important to further note that Vicksburg was also the connecting link between the eastern and western parts of the Confederacy, what Jefferson Davis referred to as "the nailhead that held the South's two halves together." In addition, the city sat astride a major Confederate supply route over which the armies of Braxton Bragg and Robert E. Lee received much-needed food, clothing, medicine, and ammunition, as well as fresh troops. It was imperative for the administration in Washington to regain control of the lower Mississippi River, thereby reopening that avenue of commerce. It would also split the Confederacy in two severing that vital supply route.

Eager to confront the difficult task before them, Union land and naval forces moved with a vengeance from two directions in a converging attack to wrestle control of the river from Confederate troops. Driving south from Cairo, Illinois, Federal forces seized Forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers respectively and opened the pathway of invasion to the Deep South. Continuing the drive, Union forces gained victory at Shiloh in April, Corinth in May, and having forced the surrender of Island No. 10, seized Memphis in June. Moving upriver from the Gulf of Mexico were the ships of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron commanded by Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut. His ships bombarded and passed Forts Jackson and St. Philip on April 24 and compelled the surrender of New Orleans. With initial success behind him, Farragut sent an advance flotilla upriver. Baton Rouge fell to the Federals on May 8, Natchez four days later, and the flotilla steamed on toward Vicksburg.

After the fall of New Orleans, as the Union pincer slowly closed along the river, the Confederates began to fortify Vicksburg. The city's geographical location made it ideal for defense. Equally important, existing rail lines which connected Vicksburg with Jackson and, via Jackson, points elsewhere in the Confederacy, enabled the shipment of heavy ordnance to the "Hill City:" It was not long before Vicksburg became known as the "Gibraltar of the Confederacy," and it would prove a tough nut to crack. The strategic significance of Vicksburg greatly increased after the fall of Memphis, as it then became the northernmost point below Memphis where the bluffs met the river. It was only a matter of time before war in all its horror centered on Vicksburg.

Michigan Battlefield Monument!

Initial efforts by Union land and naval forces to capture Vicksburg and open the great waterway to navigation ended in failure. The first threat developed on May 18, 1862, when the ships of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron arrived below Vicksburg and the Federals made a demand for the city's surrender. In terse words the demand was refused. Lieutenant Colonel James L. Autry, the post commander, replied, "Mississippians don't know, and refuse to learn, how to surrender to an enemy." Incensed, Federal authorities opened fire upon the city and maintained an intermittent bombardment from late May, all through June, and into late July, but to no avail. The bombardment was ineffective and Farragut's fleet, wracked with sickness and plagued by rapidly falling waters, withdrew to New Orleans and deeper waters. Both the Union and Confederate high commands then realized that if Vicksburg were going to fall it would be at the hands of a combined land and naval effort. The batteries that overlooked the Mississippi River at Vicksburg were powerful, but all the land accesses were open. The Confederates decided to construct a line of defense to guard the city's landward approaches and control the roads and railroad access to Vicksburg.

Due to a series of sharp narrow ridges, fronted by deep steep ravines caused by centuries of mud from the Mississippi River, Vicksburg was a natural fortress. Major Samuel Lockett, chief engineer of the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, made it even stronger by the construction of field fortifications. The line, as constructed, consisted of nine major forts connected by a continuous line of trenches and rifle pits. The line formed a huge semicircle around Vicksburg, the flanks of which rested on the river above and below the city. It would be manned by a garrison of 30,000 troops, mount 172 big guns, and pose the major challenge to Union domination of the river.

Late that same year, a two-pronged Federal advance on Vicksburg met with disaster when Major General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Union Army of the Tennessee, divided his force in two for an advance on Vicksburg. One column, under Grant's personal command, marched overland from Grand Junction, Tennessee, into north Mississippi, while the other column, under Major General William T Sherman, made a rapid push down the Mississippi River and attempted to seize Vicksburg. As Grant's column pushed south through Holly Springs and Oxford toward Grenada, his ever-lengthening supply and communications line became dangerously exposed and fell prey to raiding Confederate cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest. His advance base at Holly Springs also fell victim to raiding cavalry under Earl Van Dorn, which compelled Grant to pull back to Memphis. This regression enabled Confederate forces, utilizing interior rail lines, to rush to Vicksburg, arriving in time to thwart Sherman's strike just northeast of the city along the banks of Chickasaw Bayou. In reporting the action, Sherman simply wrote, "I reached Vicksburg at the time appointed, landed, assaulted and failed."

Checked on the overland route, Grant seized upon Federal naval supremacy on the inland waters to transfer his army to Milliken's Bend and Young's Point, Louisiana, on the Mississippi River just north of and opposite Vicksburg. During the winter months, Federal forces stockpiled tremendous quantities of rations, clothing, medicine, ammunition, and countless other items for the spring campaign aimed at Vicksburg. Grant also orchestrated a series of ill-fated bayou expeditions, the object of which was to reach the rear of Vicksburg.

Mike and Bone inside the Vicksburg Illinois Battlefield Monument

Vicksburg Battlefield

By late spring 1863, after months of frustration and failure, Grant was at a crossroads in his military career. There was tremendous clamor in the Northern press to remove him from command. Even members of the Cabinet urged Lincoln to replace Grant as commander of the western army. But the President responded to those critical of Grant by saying, "I can't spare this man, he fights. I'll try him a little longer." Aware of the clamor against him, Grant examined his options. In Grant's mind the most viable option was to march the army down the west side of the river, search for a favorable crossing point, and transfer the field of operations to the area south and east of Vicksburg. In characteristic fashion and with grim determination, Grant ordered Major General John A. McClernand of the Thirteenth Corps to open a road from Milliken's Bend to New Carthage on the Mississippi River below Vicksburg. The movement began on March 31, 1863, and thus the Vicksburg Campaign began in earnest.

As Grant's infantrymen slogged their way south through Louisiana, corduroying roads and building bridges each step of the way, the Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter prepared to run by the batteries at Vicksburg. On the dark, moonless night of April 16, Porter's vessels raised anchor and moved downriver toward the citadel of Vicksburg with engines muffled and running lights extinguished. Suddenly the night sky was ablaze from bales of cotton soaked in turpentine that lined the river on both banks and barrels of tar set afire by the Confederates to illuminate the river and silhouette the fleet as it passed the batteries. For several hours the fleet withstood the punishing fire that poured forth from Confederate batteries. When the shelling stopped, Porter tallied the damage to his fleet and recorded the loss of only one transport vessel. What many deemed impossible had been achieved. With Porter's fleet now below Vicksburg, Grant had the wherewithal to cross the mighty river. It was Grant's intention to force a crossing of the river at Grand Gulf where there was a good all-weather landing and from which point roads radiated deep into the interior of Mississippi. Two forts guarded Grand Gulf and posed an obstacle to Federal plans.

On April 29, Porter's gunboats bombarded the Grand Gulf defenses in preparation for a landing by Grant's troops. The fleet silenced the guns of Fort Wade, but could not silence those of Fort Cobun. Ever adaptive, Grant disembarked his men from the transports and marched them five miles farther down the levee. That evening, Porter's fleet passed the Confederate batteries and joined with Grant at Disharoon's plantation. From April 30 to May 1 Grant hurled his army across the mighty river and onto Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg. A band aboard the flagship Benton struck up The Red, White, and Blue as Grant's infantrymen came ashore. In one of the largest amphibious operations in American history up to that time, Grant landed 22,000 men and began the inland campaign to capture Vicksburg. Once ashore, Grant's forces pushed rapidly inland and marched through the night. In the early morning hours of May 1, they encountered Confederate resistance west of Port Gibson. In a furious battle which raged throughout the day, Union soldiers fought with grim determination to secure their beachhead on Mississippi soil while Confederate soldiers fought with equal determination to drive the invaders into the river. By day's end, the Confederate forces, outnumbered and hard-pressed, retired from the field.

Rather than march north on Vicksburg, Grant directed his army in a northeasterly direction in order to cut the rail line that connected the Hill City with Jackson and cut the Confederate garrison off from supplies and reinforcements. In a seventeen-day period, which is often referred to as the blitzkrieg of the Vicksburg Campaign, Grant's army marched more than 200 miles, and overcame Confederate resistance in five battles. The first battle occurred at Port Gibson on May 1, the second at Raymond on May 12, and the third on May 14 when the Union army captured the capital of Mississippi. Not wishing to waste combat troops on occupation,

Grant neutralized Jackson with the torch then turned west toward his objective — Vicksburg. En route from Jackson to Vicksburg, his force inflicted devastating casualties on the Confederate army commanded by Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16. On the following day, May 17, Grant soundly defeated Confederate forces in a battle at the Big Black River Bridge, hurling Pemberton's army into the defenses of Vicksburg. Having witnessed the debacle at the Big Black River and the wild flight of his troops, Pemberton dejectedly stated, "Just thirty years ago I began my military career by receiving my appointment to a cadetship at the U.S. Military Academy, and to-day — that same date — that career is ended in disaster and disgrace."

For all practical purpose it was, but it was a disaster that would affect an entire nation. The citizens of Vicksburg watched in fear as the shattered remnants of Pemberton's army poured into the city on that fateful day. Mrs. Emma Balfour stood in her doorway as the demoralized mass of humanity filled the streets. She later wrote with trepidation, "I hope never to witness again such a scene as the return of our routed army!" With pen in hand she recorded the scene which enveloped her, "From twelve o'clock until late in the night the streets and roads were jammed with wagons, cannons, horses, men, mules, stock, sheep, everything you can imagine that appertains to an army being brought hurriedly within the intrenchment." She confided to her diary the fears of many in Vicksburg as she wrote, "What is to become of all the living things in this place...shut up as in a trap...God only knows." On through the long day and into the evening marched the weary soldiers clad in butternut and gray. Singly or in small groups, with no sense of order or discipline, the men filed into the rifle-pits and turned to meet Grant's rapidly approaching army. Throughout the night, axes rang out constantly as the Confederates felled additional trees to strengthen fortifications, clear fields of fire, and form abatis in their front. Work continued at a feverish pace and, by sunrise, the city was in a good state of defense.

Late in the afternoon, May 18, Confederate soldiers peering over their parapets spotted long columns of Union infantrymen moving slowly toward the city. Federal skirmishers were quickly deployed and artillery roared into action, but the day wore away with nothing more than a long-range artillery duel. That night, as darkness enveloped the fields, the soldiers of both armies rested on their arms. Each knew that the bloody work at hand would commence with the rising sun and prepared for battle in his own way.

The Shirley House

Grant was anxious for a quick victory and, after making a hasty reconnaissance, ordered an attack. Early on the morning of May 19, Union artillery opened fire upon the city and for hours bombarded the Confederate works with solid shot and shell. At 2 p.m., when the guns fell silent, Union soldiers deployed into line of battle astride Graveyard Road, northeast of Vicksburg, and stormed the city's defenses. They succeeded in planting several stands of colors on the parapets of Vicksburg, but were driven back with the loss of 942 men.

Undaunted, Grant decided to make a more thorough reconnaissance, then hurl his entire force against Vicksburg on May 22. Early that morning, Union artillery roared into action and for four hours bombarded the works, tearing large holes in the earthen fortifications. At 10 a.m., the artillery fell silent and Union soldiers moved forward over a three-mile front toward the defenses of Vicksburg. Again they succeeded in planting their colors on the parapets of Vicksburg in several areas and made a short-lived penetration at Railroad Redoubt, but were driven back a second time with severe loss. In the assault on May 22, Grant lost more than 3,000 men killed, wounded, or missing. Although his nose had been bloodied a second time, Grant was not yet willing to toss in the towel and lay siege to the city. As he contemplated his next move, Grant left behind his dead and wounded, including many who had been lying exposed since May 19. Exposed to the sun and heat, the bodies of the dead began to bloat and turn black; the stench was sickening. On May 25, white flags appeared along the Confederate line Union soldiers were hopeful that the city would soon be surrendered. Theft hopes were dashed as word quickly spread that a note was passed from Pemberton to Grant "imploring in the name of humanity" that Grant bury his dead as the odor had become quite offensive. A truce was granted for two and one-half hours during which time men in blue and gray mingled between the lines. While the gruesome task of the burial details was completed, it was almost as if there was no war in progress. At the appointed time, however, the flags were taken down and everyone ran for cover.

The siege of Vicksburg began in earnest that day.

Captain Andrew Hickenlooper (Who?!)

Andrew Hickenlooper distinguished himself so during the Vicksburg Campaign, Brig. Gen. James McPherson wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that, as Hickenlooper's further promotion in the line of the artillery service was impossible, that he be given special consideration for promotion. He was instrumental throughout the month of May and into June, Union soldiers slowly extended their lines to the left and right until they encircled the beleaguered city, effectively cutting Pemberton's garrison off from all supply and communications with the outside word. The Confederates had to subsist solely on what they had stockpiled in Vicksburg prior to the siege. In order to conserve what food supplies were on hand, Pemberton ordered the daily ration cut to three quarters, then to half, then to quarter, then they were cut again, and yet again. By the end of June the garrison was issued only a handful of peas and rice per man per day. Even their water was rationed.

As May slowly faded into June, Union soldiers began to dig approaches toward the Confederate line. Forming first zigzag trenches to frustrate enemy fire and then parallels, Grant moved up his infantry and artillery first to within 300 yards, then 200 yards, then 100 yards. The digging continued as Union soldiers worked their way up to the parapets of Vicksburg. Their object was to get as close as possible, then tunnel underneath the enemy works, hollow out rooms, fill them with black powder, and blow them up, hopefully destroying the fortifications of Vicksburg. Union soldiers excavated thirteen approaches at different points along the siege line; the most successful of which was known as "Logan's Approach." Situated along the Jackson road, Logan's Approach inched forward toward the Third Louisiana Redan. Excavating or trench that was seven feet deep and eight feet wide, Union fatigue parties reached the Third Louisiana Redan on June 23. They carved a gallery directly under the fort and made preparations for mining.

On June 25, 2,200 pounds of black powder were placed in the mine. At 3 p.m. the fuse was lit. Tense moments passed as the Federals waited to storm into the breach and seize Vicksburg. Suddenly there was a muffled thud, then a loud bang as the ground began to break and an enormous column of flame and dirt exploded upwards, carrying men, mules, and accoutrements to the sky. Before the dust could even settle, Union soldiers poured into the crater and attempted to secure the breach. In the wild mêlée that ensued, the men freely used clubbed muskets and bayonets and tossed hand grenades back and forth. The battle raged in unabated fury for twenty-six hours as Grant threw in one fresh regiment after another, all to no avail. The breach was sealed by the Confederates at the point of bayonet. The great gamble had failed.

Undaunted, the Federals planted a second mine and detonated it on July 1— but they did not follow it up with an infantry assault. That day, Grant was notified by his subordinates that given just a few more days of digging, thirteen mines could be planted and detonated simultaneously. This was the moment Grant and his army had been working toward all these many weeks of siege. It is not likely that the Confederates could have withstood such an attack.

The Vicksburg Battlefield African-American Monument

On the hot afternoon of July 3 Grant was in the process of planning an attack (which he scheduled for July 6), when white flags of truce again appeared along the lines. Riding out from the city came a cavalcade of officers in gray led by General Pemberton. Grant rode to meet with him between the lines. Pemberton asked Grant on what terms would he receive the surrender of the garrison and city of Vicksburg. Grant replied that he had no terms other than immediate and unconditional surrender. These terms were unacceptable to Pemberton who assured Grant that he would bury many more of his men before he gained entrance to Vicksburg. The generals agreed only upon a cessation of hostilities, then rode their separate ways. Grant assured Pemberton that he would have his final terms by ten o'clock that night.

True to his word, Grant sent in his final, amended terms. Instead of an unconditional surrender of Vicksburg, Grant offered parole to the garrison. Pemberton received the note in the quiet of his headquarters. In the company of his generals, Pemberton read the note then passed it around for his subordinates to read and comment upon. Almost to a man, these agreed they were the best terms to be had.

On the morning of July 4, 1863, white flags fluttered in the breeze above the fortifications of Vicksburg. Marching out from their works, Confederate soldiers furled their flags, stacked their arms, and turned over their accouterments. A victorious Union army marched in and took possession of Vicksburg — the fortress city on the Mississippi River that had eluded them for so long.

Grant rode into the city along the Jackson Road and down to the Warren County Courthouse where he watched the Stars and Stripes raised above the building. He then rode down to the waterfront where he personally thanked and congratulated Admiral Porter for the assistance rendered by the United States Navy during the operations for Vicksburg. Almost as an afterthought, he sent a message to Washington informing President Lincoln of the city's surrender. It took several days for the message to reach the capital during which time the only remaining Confederate bastion on the Mississippi River — Port Hudson, Louisiana — fell into Union hands. Upon receipt of Grant's message, Lincoln sighed, "Thank God," and declared "The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea."

General Grant!

Mr. Joe told the story with passion and flourish and shared some interesting insights from a Confederate's descendant's perspective. Before the Civil War, Mississippi was one of the top three richest states. With the loss of their slaves the immediately plummeted to the bottom, to where they still sit. In fact of all the southern states, Mississippi was the most affected financially.

The hills and slopes from the floods of the Mississippi River

The geology of Vicksburg, helped both the Confederates and the Union. The Confederates used it for defensive purposes, and the Union used it to hide its movements.

Less than Pugnacious Lt. General John C. Pemberton!

John C Pemberton the Confederate Commander didn't have a good time at Vicksburg. On the evening of July 2, 1863, Pemberton asked in writing his four division commanders if they believed their men could "make the marches and undergo the fatigues necessary to accomplish a successful evacuation" after 45 days of siege. With four votes of no, the next day Pemberton asked the Federals for an armistice to allow time for the discussion of terms of surrender, and at 10:00 a.m. on July 4 he surrendered the city and his army to Grant. The written terms (which in the first talks were simply unconditional surrender) were negotiated so that the Confederate soldiers would be paroled and...be allowed to march out of our lines, the officers taking with them their side-arms and clothing, and the field, staff, and cavalry officers one horse each. The rank and file will be allowed all their clothing, but no other property.

Jefferson Davis, the Traitor!

Not sure why there is a statue of Jefferson Davis at Vicksburg, Mike and Bone aren’t sure, other than he was a Democratic U.S. senator from Mississippi. He was an operator of a large cotton plantation in Mississippi with over 100 slaves and was well known for his support of slavery in the Senate. Ironically He argued against secession, but did agree that each state was sovereign and had an unquestionable right to secede from the Union. His intransigence in making Pemberton stay in Vicksburg and lose his army to Grant’s superior Union army, probably speeded up the final collapse of the Confederacy.

Lieutenant General Stephen Dill Lee

Stephen Dill Lee (no relationship to Robert E. Lee) was the youngest Lieutenant General in the Confederacy and had a distinguished record in some of the highest profile battles. It could be said that he started the Civil War since he delivered an ultimatum from Beauregard to Union Maj. Robert Anderson, demanding the evacuation of Fort Sumter, which was refused and after bombardment the fort fell on April 14, precipitating the start of the War. During the Vicksburg Campaign, Lee briefly led an infantry division during the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou from December 26–29 1862, where he repulsed the attacks of Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. Beginning in January 1863 he led a brigade in the Department of Mississippi & Eastern Louisiana until that May, when he was ordered to take command of Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton's artillery defending access to the Mississippi River at Vicksburg. Lee fought notably during the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, where he was wounded when he was hit in a shoulder. Military historian Jon L. Wakelyn praises Lee's performance in this action, saying "he was the hero of the battle of Champion Hills." Lee continued to serve throughout the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg until Pemberton's surrender to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, becoming a prisoner of war.

The Classic Southern Oak with Spanish Moss

The Ironclad U.S.S Cairo

The U.S.S. Cairo was one of seven ironclad gunboats named in honor of towns along the upper Mississippi and Ohio rivers. These powerful ironclads were formidable vessels, each mounting thirteen big guns (cannon). On them rested in large part, Northern hopes to regain control of the lower Mississippi River and split the Confederacy in two. The "city class" gunboats were designed by Samuel M. Pook and built by river engineer James B. Eads. Cairo was constructed at Mound City, Illinois, and commissioned in January 1862. The Cairo was destined to see only limited action in the engagement at Plum Point in May and in the battle of Memphis in June. Her most significant action came six months later when she kept a rendezvous with destiny.

The Cairo's skipper, Lt. Commander Thomas O. Selfridge, Jr., was rash and ambitious, a stern disciplinarian, but an aggressive and promising young officer. On the cold morning of December 12, 1862, Selfridge led a small flotilla up the Yazoo River, north of Vicksburg, to destroy Confederate batteries and clear the channel of torpedoes (underwater mines). As the Cairo reached a point seven miles north of Vicksburg the flotilla came under fire and Selfridge ordered the guns to ready. As the gunboat turned towards shore disaster struck. Cairo was rocked by two explosions in quick succession which tore gaping holes in the ship's hull. Within twelve minutes the ironclad sank into six (6) fathoms (36 feet) of water without any loss of life. Cairo became the first ship in history to be sunk by an electrically detonated torpedo. Over the years the gunboat was soon forgotten and her watery grave was slowly covered by a shroud of silt and sand. Impacted in mud, Cairo became a time capsule in which her priceless artifacts were preserved. Her whereabouts became a matter of speculation as members of the crew had died and local residents were unsure of the location.

By studying contemporary documents and maps, Edwin C. Bearss, Historian at Vicksburg National Military Park, was able to plot the approximate site of the wreck. With the help of a pocket compass and iron bar probes, Bearss and two companions, Don Jacks and Warren Grabau, set out to discover the grave of the Cairo in 1956. The three searchers were reasonably convinced they had found the Cairo, but three years lapsed before divers brought up armored port covers to positively confirm the find. A heavy accumulation of silt, swift current, and the ever-muddy river deterred the divers as they explored the gunboat. Local enthusiasm and interest began to grow in 1960 with the recovery of the pilothouse, an 8-inch smoothbore cannon, its white oak carriage and other artifacts well preserved by the Yazoo mud. With financial support from the State of Mississippi, the Warren County Board of Supervisors and funds raised locally, efforts to salvage the gunboat began in earnest.

Hopes of lifting the ironclad and her cargo of artifacts intact were crushed in October of 1964 when the three inch cables being used to lift the Cairo cut deeply into its wooden hull. It then became a question of saving as much of the vessel as possible. A decision was made to cut the Cairo into three sections. By the end of December the battered remains were put on barges and towed to Vicksburg. In the summer of 1965 the barges carrying the Cairo were towed to Ingalls Shipyard on the Gulf Coast in Pascagoula, Mississippi. There the armor was removed, cleaned and stored. The two engines were taken apart, cleaned and reassembled. Sections of the hull were braced internally and a sprinkler system was operated continually to keep the white oak structural timbers from warping and checking.

In 1972, the U.S. Congress enacted legislation authorizing the National Park Service to accept title to the Cairo and restore the gunboat for display in Vicksburg National Military Park. Delays in funding the project halted progress until June of 1977, when the vessel was transported to the park and partially reconstructed on a concrete foundation near the Vicksburg National Cemetery. The recovery of artifacts from the Cairo revealed a treasure trove of weapons, munitions, naval stores and personal gear of the sailors who served on board. The gunboat and its artifacts can now be seen along the tour road at the U.S.S. Cairo Museum.

Looking up at the Bluffs the Confederates Defended

Vicksburg Battlefield National Cemetery

Next Mike and Bone with reverence checked out the Vicksburg National Cemetery, which is 116 acres, and holds the remains of 17,000 Civil War Union soldiers, a number unmatched by any other national cemetery. Covering ground once manned by the extreme right of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's XV Army Corps during the siege of Vicksburg, it was established by an act of Congress in 1866, and serves as the final resting place for United States soldiers who gallantly served this country in times of national and international conflict. During the Civil War, soldiers that succumbed to wounds or disease were typically buried close to where they died. If their name was known, their grave could be marked with whatever materials were at hand — most commonly the etching of the name into a wooden board.

After the creation of Vicksburg National Cemetery, extensive efforts were made by the War Department to locate the remains of Union soldiers originally buried throughout the southeast in the areas occupied by Federal forces during the campaign and siege of Vicksburg — namely, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. However, by the time of these re-interments many of the wooden markers had been lost to the elements, and identification of many of the soldiers was rendered impossible. Others who died during the Federal occupation of Vicksburg were buried at various points in the Vicksburg vicinity prior to the cemetery's establishment. Record-keeping was haphazard under wartime conditions and these grave locations were often lost. Following the Civil War, the U.S. Army located and exhumed the remains of 300,000 Union soldiers buried in the South, re-interring the remains in national cemeteries throughout the country.

No one of national fame is buried in Vicksburg National Cemetery, with Brevet Brig. Gen. Embury D. Osband qualifying as the highest-ranking veteran interred (Grave #16648, Section O). In the late 1860's, two Confederates were mistakenly buried in Section B of the cemetery (Private Reuben White, 19th Texas Infantry Regiment, Grave #2637; Sergeant Charles B. Brantley, 12th Arkansas Sharpshooters Battalion, Grave #2673).

Discovering De Soto!!!

One of the cool things Mr. Joe showed Mike and Bone at the National Park was the infamous Spanish Conquistador, Hernando De Soto! Floating down the Mississippi River in the Summer of 1543, having spent four years plundering America, De Soto's 320 Spaniards in seven brigantines were making their 666 mile downstream escape to the Gulf of Mexico, averaging 50 miles per day (river flow rate is 65 miles per day), some longer, some shorter. They stopped to rest for five or six hours most nights at favorable river landings and bends along their way. One of De Soto's men that chronicled the trip, Elvas stated "...when they reached a town near a bluff (current day Vicksburg), the local Indians all united, as if to show that they were a mind to wait there and attack the Spaniards. There, the Spaniards built a Fort for which the foundations still exist all these years later in the Vicksburg Battlefield National Park!

Checking it out gave the Boys a great view of the "bend" in the Mississippi River that gave Vicksburg's Confederate defenders a great advantage.

At the Bend in Mighty M!!!

C'Yah Joe !

Mr. Joe gave the Boys a full three hours and earned every penny! Mike and Bone bid him a fond adieu!! Next, time to check out Oxford and Ole Miss! Since it is was a two hour drive, the Boys filled the ubiquitous Hall of Shame with delicious malted grain beverages of the micro-brew kind for the ride. Between the jabbering on the National Park, the Civil War, and the Blues, the Boys were pulling into Oxford !

R U Ready for some SEC Football!

Old Men at Ole Miss!

The University of Mississippi and Oxford is known as being one of the prettiest campus in the country, and from the Boys point of view it didn't disappoint! On top of the very cool Running Rebels Stadium, with Oxford's restaurants, and oak-shaded neighborhoods, it is considered the model Southern town. Named after Oxford, England in hopes of attracting a university, the town was selected as the home of the University of Mississippi in 1848. Oxford served as the inspiration for Nobel Prize winner William Faulkner's fictional Jefferson, the locale of many of his novels.

Wearing Out Oxford!

The Awesome Campus of Ole' Miss!

Townies and students describe the town with the motto "We may not win every game, but we never lose a party." Locals also, "partially" jokingly, refer to the Square as the "Center of the Universe." Many residents see Oxford as a small town New Orleans, calling it the "Little Easy." It is widely known throughout the South for its Southern charm, Old South feel, and its party atmosphere. Oxford is also considered a literary center with many writers calling it home. Also being home to the Ole Miss School of Law and a federal courthouse, it is often said that everyone in Oxford is a "lawyer, writer, or both." As if to prove this point, famous author John Grisham still owns a house in Oxford and visits frequently.

Mike and Bone, doing was College Boys do! Drinking!

The Square is the center of downtown and is the main location for the town's best restaurants, shops, bars, and scenery. Mike and Bone decided to do a mini-pub crawl. Keep in mind it was still winter time, but the Boys were drinking outside at several of the better College Bars. Bone was very proud of his University of Michigan Hawaiian Shirt as the REAL U of M!

Ready !,, Set !!

,,, Go !!!

Regardless, the college co-eds found the old men cute,flirted and took the Boys pictures as they had an old fashion drink off ! Unfortunately it was getting late in the afternoon and the sun as starting to drop. Around 6:00 the Boys had to bid adieu the lovely college town as head back to Memphis.

Trip, Postscript

Mike and Bone got back to Memphis around 11:00PM, pretty beat from a long day of driving, site seeing, and drinking in the College Bars. They decided to not go fancy and grabbed a Motel 6 just next to the Memphis Airport since they both had early flights the next day.

The Memphis Airport is in a bad part of town, and the Motel was not very good.

Or better put, the type of place Joliet Jake and Elwood would flop for the night!

The next morning Mike and Bone had un-cool McDonald Breakfast Burritos and belched the blues on their flights home, a fitting end to the Blues Brother Tour!!!