Main Page > 2013 Bone's Last Stand ! >

The 1970's Progressive Band King Crimson came out in the mid-80's with a song "Three of a Perfect Pair", which was apropos since the Boys intended to hit three National Parks in to really big states in one day! So rising early Mike and Bone beat a path as fast as possible outta Hardin and down to the Little Big Horn as soon as it opened. It was already a scorching hot day at 8:30 when the Boys entered the National Park!

The Spot where George Armstrong Custer fell on Last Stand Hill!

So where to start on such an epic Battle?!? There are few American Battles that have been discussed, viewed, hyperboled, and opinioned more that the Battle of the Little Big Horn. So first thing the Boys did is to check out the Museum to check out at least one of the stories.

Custer, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse; Mike and Bone?

Tension between the Lakota Sioux and the Northern Cheyenne and the American Military resulted in a series of conflicts known as the Sioux Wars. Even though many agreed to relocate to ever-shrinking reservations, some resisted. In 1875, Sitting Bull created the Sun Dance alliance between the Lakota and the Cheyenne and a large number of "Agency Indians" who had slipped away from their reservations to join them. To incent Sitting Bull onto a Reservation in 1876 General Sherman committed his troops to a summer campaign to force the Lakota and Cheyenne back to their reservations, using infantry and cavalry in a three-pronged approach. Col. John Gibbon's column of six companies of the 7th Infantry and four companies of the 2nd Cavalry marched east from Fort Ellis in western Montana on March 30, to patrol the Yellowstone River. Brig. Gen. George Crook's column of ten companies of the 3rd Cavalry, five of the 2nd Cavalry, two companies of the 4th Infantry, and three companies of the 9th Infantry, moved north from Fort Fetterman in the Wyoming Territory on May 29, marching toward the Powder River area. Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry's column, including twelve companies of the 7th Cavalry under Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer's immediate command departed westward from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory on May 17.

Last Stand Hill? Maybe not!

The coordination and planning began to go awry on June 17, 1876, when Crook's column retreated after the Battle of the Rosebud. Surprised and, according to some accounts, astonished by the unusually large numbers of Native Americans in the battle, Crook held the field at the end of the battle but felt compelled by his losses to pull back, regroup and wait for reinforcements. Unaware of Crook's battle, Gibbon and Terry proceeded, joining forces in early June near the mouth of the Rosebud Creek. They reviewed Terry's plan calling for Custer's regiment to proceed south along the Rosebud, while Terry and Gibbon's united forces would move in a westerly direction toward the Bighorn and Little Bighorn rivers. As this was the likely location of Native encampments, all army elements were to converge around June 26 or 27, attempting to engulf the Native Americans. On June 22, Terry ordered the 7th Cavalry, composed of 31 officers and 566 enlisted men under Custer, to begin a reconnaissance and pursuit along the Rosebud, with the prerogative to "depart" from orders upon seeing "sufficient reason."

While the Terry/Gibbon column was marching toward the mouth of the Little Bighorn, on the evening of June 24, Custer's scouts arrived at an overlook known as the Crow's Nest, 14 miles east of the Little Bighorn River. At sunrise on June 25, Custer's scouts reported they could see a massive pony herd and signs of the Native American village roughly 15 miles in the distance. After a night's march, the tired officer who was sent with the scouts could see neither, and when Custer joined them, he was also unable to make the sighting. Custer contemplated a surprise attack against the encampment the following morning of June 26, but he then received a report informing him several hostiles had discovered the trail left by his troops. Assuming his presence had been exposed, Custer decided to attack the village without further delay. On the morning of June 25, Custer divided his 12 companies into three battalions in anticipation of the forthcoming engagement. Three companies were placed under the command of Major Marcus Reno; and three were placed under the command of Capt. Frederick Benteen. Five companies remained under Custer's immediate command.

Unknown to Custer, the group of Native Americans seen on his trail were actually leaving the encampment on the Big Horn and did not alert the village. Custer's scouts warned him about the size of the village, with Mitch Bouyer reportedly saying, "General, I have been with these Indians for 30 years, and this is the largest village I have ever heard of." Custer's overriding concern was that the Native American group would break up and scatter. The command began its approach to the village at noon and prepared to attack in full daylight.

Custer's field strategy was designed to engage noncombatants at the encampments at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, so as to capture women, children, the elderly or disabled to serve as hostages and human shields. Custer's battalions were poised to "ride into the camp and secure noncombatant hostages" and "force the warriors to surrender". The theory is that if Custer could occupy the village before widespread resistance developed, the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors "would be obliged to surrender, because if they started to fight, they would be shooting their own families."

As Custer moved into the Battle, it was operating with incorrect assumptions as to the number of Indians they would encounter. Custerís assumptions were based on inaccurate information provided by the Indian Agents that no more than 800 hostiles were in the area. The Indian Agents based the 800 number on the number of Lakota led by Sitting Bull and other leaders off the reservation in protest of US Government policies. This was a correct estimate until several weeks before the battle, when the "reservation Indians" joined Sitting Bull's ranks for the summer buffalo hunt. However, the agents did not take into account the many thousands of "reservation Indians" who had "unofficially" left the reservation to join their "uncooperative non-reservation cousins led by Sitting Bull". The latter were those groups who had indicated that they were not going to cooperate with the US Government and live on reservation lands. Thus, Custer unknowingly faced 5,000 to 8,000 thousand Indians!

The Direction that the Indians swarmed Custer's Command

Additionally, Custer was more concerned with preventing the escape of the Lakota and Cheyenne than with fighting them. From his own observation, as reported by his bugler John Martin, Custer assumed the warriors had been sleeping in on the morning of the battle, to which virtually every native account attested later, giving Custer a false estimate of what he was up against. When he and his scouts first looked down on the village from Crow's Nest across the Little Bighorn River, they could only see the herd of ponies.

Looking from a hill 2.5 miles away after parting with Reno's command, Custer could observe only women preparing for the day, and young boys taking thousands of horses out to graze south of the village. Custer's Crow scouts told him it was the largest native village they had ever seen. When the scouts began changing back into their native dress right before the battle, Custer released them from his command. While the village was enormous in size, Custer thought there were far fewer warriors to defend the village. He assumed most of the warriors were still asleep in their tipis.

Custerís Battle Plan was for Major Reno to go into the Village on horseback and attack riding through it. Custer would take troops around the Village and attack from behind, using a classic pincer movement to confuse and frighten the ďsmallĒ village into surrendering. It was a technique Custer had used before in Indian fighting, why wouldnít it work this time?

Meanwhile Major Benteen would be waiting in reserve, if needed.

The 7th Cavalry Moment to the 210 Dead Soldiers

Per Custerís orders Major Reno's started the attack after receiving orders from Custer written out by Lt. William W. Cooke, as Custer's Crow scouts reported Sioux tribe members were alerting the village. Ordered to charge, Reno began that phase of the battle. The orders, made without accurate knowledge of the village's size, location, or the warriors' propensity to stand and fight, had been to pursue the Native Americans and "bring them to battle." Reno's force crossed the Little Bighorn at the mouth of what is today Reno Creek around 3:00 pm.

They immediately realized that the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne were present "in force and not running away." Reno advanced rapidly across the open field towards the northwest, his movements masked by the thick bramble of trees that ran along the southern banks of the Little Bighorn River. The same trees on his front right shielded his movements across the wide field over which his men rapidly rode, first with two approximately forty-man companies abreast and eventually with all three charging abreast. The trees also obscured Reno's view of the Native American village until his force had passed that bend on his right front and was suddenly within arrow shot of the village. The tepees in that area were occupied by the Hunkpapa Sioux. Neither Custer nor Reno had much idea of the length, depth and size of the encampment they were attacking, as the village was hidden by the trees.

When Reno came into the open in front of the south end of the village, he sent his Arikara and Crow Indian scouts forward on his exposed left flank. Realizing the full extent of the village's width, Reno quickly suspected what he would later call "a trap" and stopped a few hundred yards short of the encampment. Contrary to Custer's orders, Reno ordered his troopers to dismount and deploy in a skirmish line, according to standard army doctrine. In this formation, every fourth trooper held the horses for the troopers in firing position, with five to ten yards separating each trooper, officers to their rear and troopers with horses behind the officers. This formation reduced Reno's firepower by 25 percent. As Reno's men fired into the village and killed, by some accounts, several wives and children of the Sioux leader, Chief Gall, mounted warriors began streaming out to meet the attack. With Reno's men anchored on their right by the impassable tree line and bend in the river, the Indians rode hard against the exposed left end of Reno's line. After about 20 minutes of long-distance firing, Reno had taken only one casualty, but the odds against him had risen (Reno estimated five to one) and Custer had not reinforced him. Trooper Billy Jackson reported that by then, the Indians had begun massing in the open area shielded by a small hill to the left of the Reno's line and to the right of the Indian village.

From this position the Indians mounted an attack of more than 500 warriors against the left and rear of Reno's line, turning Reno's exposed left flank. They forced a hasty withdrawal into the timber along the bend in the river. Here the Indians pinned Reno and his men down and set fire to the brush to try to drive the soldiers out of their position.

After giving orders to mount, dismount and mount again, during this bizarre sequence Reno's Arikara Scout Bloody Knife, was shot in the head as he sat on his horse next to Reno and his blood and brains splattering the side of Reno's face. The totally unnerved Reno told his men, "All those who wish to make their escape follow me," and led a disorderly rout across the river toward the bluffs on the other side. The retreat was immediately disrupted by Cheyenne attacks at close quarters. Later Reno reported that three officers and 29 troopers had been killed during the retreat and subsequent fording of the river, with another officer and 13Ė18 men missing. Most of these men were left behind in the timber, although many eventually rejoined the detachment. Atop the bluffs, known today as Reno Hill, Reno's shaken troops were joined by Captain Benteen's column, arriving from the south. This force had been on a lateral scouting mission when it had been summoned by Custer's messenger, Italian bugler John Martin with the hand-written message "Benteen. Come on, Big Village, Be quick, Bring packs. P.S. Bring Packs." Benteen's coincidental arrival on the bluffs was just in time to save Reno's men from possible annihilation, but may have doomed Custer's men. Their detachments were reinforced by McDougall's Company B and the pack train. The 14 officers and 340 troopers on the bluffs organized an all-around defense and dug rifle pits using whatever implements they had among them, including knives. This practice had become standard during the last year of the American Civil War, with both Union and Confederate troops utilizing knives, eating utensils, mess plates and pans, to dig effective battlefield fortifications.

With Reno cowering on the hill, the Indians heard of another American attack coming from the north of the Village, Custerís 210 men. With the warriors whipped into a frenzy, Crazy Horse led most likely 1,200 warriors against Custer small group. Custerís last stand didnít take more (per the Indians who recounted the battle years later) more that 20-30 minutes. It really wasnít much of a stand. It is quite likely that Custer did not even see the route. There are a number of Indian stories that Custer was shot in the temple and died crossing the river. Where he was found was probably a result of where his horse fell after his death. The action on Last Chance Hill did show that there were some pockets of resistance with horses shot by the trooper in order to hide behind them. There is also evidence that a final pocket of American resistance tried in futility to escape down the hill.

The Spot where Crazy Horse circled, flanked, (and filleted!) Custer's Troops

Meanwhile, after the Custer was annihilated, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne regrouped to attack Reno and Benteen. The fight continued until dark (approximately 9:00 pm) and for much of the next day, with the outcome in doubt. Reno credited Benteen's leadership with repulsing a severe attack on the portion of the perimeter. On June 27, the very late (remember the bigger strategy!?) column under General Terry approached from the north, and the Indians drew off in the opposite direction. The Crow scout White Man Runs Him was the first to tell General Terry's officers that Custer's force had "been wiped out."

So who is at fault? History may never tell. Clearly the Government needed a scapegoat and the dead Custer was an easy target. Plus, the Indians under Crazy Horse, did not go as easy as Indians typically would have, so was it as much of Custerís defeat or an Indian Victory? Finally, while ALL American leadership seemed to bear some responsibility. Renoís decision to not charge through the Village and then retreat certainly bears a lot of scrutiny.

The Indian Tribes Monument of who fought at the Little Big Horn

The Rolling Hills of the Sioux "Greasy Grass!

The Boys coulda spent a week there checking out the place, however destiny called Custer, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and now Mike and Bone who had two more places to hit!

The trip now took the Boys North to I-94 (yeah! Ann Arbor's I-94!) East to the Badlands of North Dakota. Of course a replenishment of the Hall of Shame was necessary. However this wasn't Kansas Dorothy, and find ANYTHING in eastern Montana proved to be an hour long ordeal until the Boys settled for McDonald's and cheap American Beer! This part of the trip was drive through fairly boring prairie until the landscape turned to weird-lookin' buttes, then dang-near moonscapes; the Badlands !! By now it was pushing 2:00 Mountain Time (important for later) and the Boys agonized about a National Historic Site stop. But since they had checked out this Presidents birthplace on 20th street in NYC, they decided on a 10 minute "speed tour" of Theodore Roosevelt's North Dakota Bad Land Cabin!

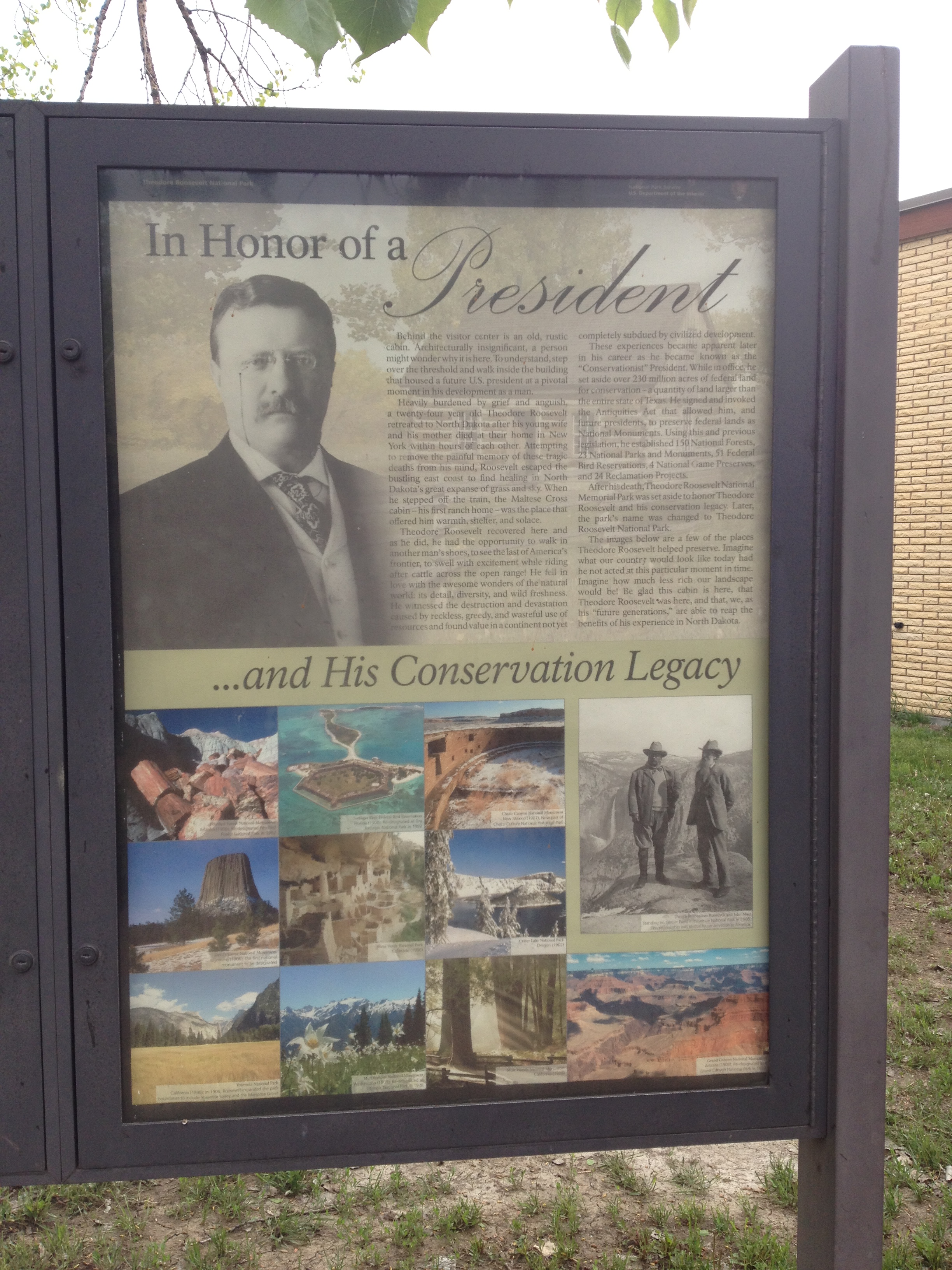

TR's Badlands Museum

As Mike and Bone pulled into the Park they ran into the Museum and read that it was here in these wild, North Dakota badlands in 1883 that Theodore Roosevelt first arrived to hunt a buffalo. Then TR (as he was called) was a skinny, young, spectacled dude from New York. He could not have imagined how his adventure in this remote and unfamiliar place would forever alter the course of the nation.

The rugged landscape and strenuous life that TR experienced here would help shape a conservation policy that we still benefit from today. Roosevelt first came to the North Dakota badlands to hunt bison in September 1883. During that first short trip, he got his bison and fell in love with the rugged lifestyle and the "perfect freedom" of the West. He invested $14,000 in the Maltese Cross Ranch, which was already being managed by Sylvane Ferris and Bill Merrifield seven miles south of Medora. That winter, Ferris and Merrifield built the Maltese Cross Cabin.

After his wife and mother died in 1884, only hours apart on February 14th, Roosevelt was absolutely devastated. He turned his back on his life in the east and moved to his North Dakota ranch seeking solitude and time to heal. That summer, he started his second ranch, the Elkhorn Ranch, 35 miles north of Medora, which he hired two Maine woodsmen, Bill Sewall and Wilmot Dow, to operate. Teddy Roosevelt took great interest in his ranches and in hunting in the West, detailing his experiences in pieces published in eastern newspapers and magazines.

He wrote three major works on his life in the West: "Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail," "Hunting Trips of a Ranchman," and "The Wilderness Hunter." His adventures in "the strenuous life" outdoors and the loss of his cattle in the starvation winter in 1886-1887 were influential in Theodore Roosevelt's pursuit of conservation policies as President of the United States In 1901, at the dawn of the 20th century, Theodore Roosevelt became the nation's 26th President and ultimately one of its greatest conservationists. He later said, "I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota."

After 5 minutes the Boys just about sprinted (definitely trotted) down to TR's Cabin out back.

Checking out TR's Joint: Maltese Cross Ranch Cabin !

TR's Spartan Abode

Mike and Bone found the Maltese Cross Ranch cabin about 50 yards in the back and was originally located about seven miles south of Medora in the wooded bottom-lands of the Little Missouri River. At Roosevelt's request, ranch managers Sylvane Ferris and Bill Merrifield built a 1 1⁄2-story cabin complete with a shingled roof and root cellar. Constructed of durable ponderosa pine logs, the cabin was considered somewhat of a "mansion" in its day, with wooden floors and three separate rooms (kitchen, living room and Roosevelt's bedroom). The steeply pitched roof, an oddity on the northern plains, created an upstairs sleeping loft for the ranch hands.

Several items present in the cabin today did belong to Theodore Roosevelt, but the majority of the furnishings are period pieces representing a typical cabin of the time. The white hutch in the main room is original to the cabin and was used as a bookcase and writing desk. The classically styled desk is from the Elkhorn Ranch cabin. Roosevelt spent many hours laboring at his desks recording his experiences and memoirs of badlands life.

The common rocking chair is believed to have been Roosevelt's, or may have come from an upstairs room in the Ferris Store where Roosevelt stayed on occasion. Rocking chairs were his favorite piece of furniture, all of his homes had rocking chairs, and Roosevelt once wrote, "What true American does not enjoy a rocking-chair?"

Roosevelt's traveling trunk sits in the bedroom and is inscribed with his initials. The large leather trunk traveled back and forth with him on the train from his home in New York City to the stop in Medora and would have held clothing and personal items.

The incredible North Dakota Badlands behind the Cabin

Roosevelt actively ranched in the badlands only until early 1887, but maintained ranching interests in the area until 1898. Later, as president, he developed a conservation program that deeply reflected his many experiences in the West. It was through these experiences that he became keenly aware of the need to conserve and protect natural resources.

During Roosevelt's presidency, the Maltese Cross cabin was exhibited at the World's Fair in St. Louis, Missouri and at the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in Portland, Oregon in 1905. In 1910, it was moved again, this time, to the state fair grounds in West Fargo, North Dakota and then eventually on the state capitol grounds in Bismarck where it remained until 1959 before the cabin was relocated to its present site and renovated. The most recent preservation work occurred in 2000.

Having "ran" through the Museum and "sprinted" through the Cabin, the Boys toured the TR's pad in 15 minutes! Back on the Road!

Barreling East through the North Dakota Badlands!

By now it was hitting 3:30 PM , it was 3 hours to Mandan (20 minutes north of Bismarck) North Dakota and its a long state!, The Boys are huge fans of Lewis and Clark. They have a whole Tour dedicated to the Voyage Discovery in the Bitterroots of Idaho. One of Lewis and Clarks first and major stops was their first Winter they spent at Fort Mandan. The Forts hours are 9:00 to 5:00 PM, Since it was the final stop on the History Trifecta , they wanted to get there before it closed.

So, Mike and Bone planned on Warp Speed, however Nature, being the cruel bitch she can be had her own idea!

Strange Brew!

As the RPM's revved in the Rental, the MPH climbed the Boys prepared for Warp speed, when the sky darkened dramatically and drastically to the point Mike hadda put on the lights ! Soon the wind started the car back and forth, then the rain came down in torrents to the point that the car was leaving a wake like a boat!!!

The drive went from a fun lark to a tense white-knuckled race against the clock! Mike was masterful in weaving in and out of traffic, making up time.

Then as the got close the gas gauge was dipping down to zero! The last 20 miles the tank was past "E" finally, there it was... Fort Mandan and the had a full ten minutes to spare!

The Times they are a Changing !

Bob Dylan

It was great, Mike and Bone made it ! They could tour Fort Mandan in 10 minutes, they had done it before! Now there wasn't a lot of cars in the parking lot, but it was pouring rain, so Mike and Bone thought nothing of it.

As they ran up to the door to make sure they got in a man and woman were coming out, and they ask the Boys, "where are your going, we are closed!"

What !? How?! What is going on!

Then the Guy said "The Fort closes at 5:00 its almost 6:00!" What !?!?

What the Boys didn't realize is right before Bismarck, you move from Mountain to Central Time!!!

Now what ? Mike and Bone don't know defeat, they spit on defeat, so they put on their saddest faces and told the two, that they had raced (only a little stretch) from Denver to Mandan only to be told they were closed.

The Park People said, "well come back tomorrow", Bone said (only a little stretch) that he was leaving the next day for Japan, with sad eyes. The Guy looked at the woman, and said "I'll take care of this" and gave the Boys a tour.......... for free!

Mike and Bone, Soaking in Fort Mandan!

First thing the very nice gentleman shared was the history of Lewis and Clark at this site. Fort Mandan was the name of the encampment which the Lewis and Clark Expedition built for wintering over in 1804-1805. The encampment was located on the Missouri River approximately twelve miles from the site of present-day Washburn, North Dakota, which developed later. The precise location is not known for certain and is believed now to be under water of the river.

The current Fort is a replica that was built by the Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation. It was re-built according to materials and design as described in the expedition's journals, it is located near the North Dakota Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center. The fort replica holds original items, such as "Meriwether Lewis' field desk, William Clark's map-making tools, bunks the men slept in, equipment they carried in the field, clothes they wore, and the blacksmith's forge." In addition, the site has personnel for tours and interpretive programs about the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its significance in United States, state and regional history. Walking trails go along the property and the river.

Fort Mandan's Front Gate

Lewis and Clark built Fort Mandan from the cottonwoods cut from the riverbanks of the broad Missouri River. It was triangular in shape, with high walls on all sides, an interior open space between structures, and a gate facing the Missouri River, by which the party would normally travel. Storage rooms provided a safe place to keep supplies. Lewis and Clark shared a room. The men of the Corps of Discovery started the fort on November 2, 1804. They wintered there until April 7, 1805.

According to the journals, they built the fort slightly downriver from the five villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa nations. The winter was very cold, with temperatures sometimes dipping to minus 45 degrees Fahrenheit (-43įC), but the fort provided some protection from the elements. Several of the men of the expedition suffered frostbite due to the severely cold conditions, which affected them even with brief exposure.

Tight Quarters

In addition to seeking protection during the winter, Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark spent much of this period on diplomatic efforts with the several Native American tribes who lived near the fort. As the expedition established the first official contact between the United States and these nations, President Thomas Jefferson had directed the captains to pursue diplomatic goals. They were to try to establish friendly relationships with as many tribes as possible, and to prepare them for the arrival of United States traders to the region.

They were also to claim United States territorial sovereignty over the land, which had been occupied by Native Americans for thousands of years. The historic tribes had differing conceptions of property use than did the European Americans. The Sioux people had already shown resistance to the expedition. Lewis and Clark gradually adjusted their goals, working to form alliances with the Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan against the Sioux. The Mandan were cautiously favorable toward such an alliance.

Lewis & Clark's "Office"

When the Expedition returned to the area in 1806 while traveling east, the Mandan sent one of their chiefs, Sheheke, on the trip to Washington, D.C. to meet with Thomas Jefferson. But, the Mandan did not commit to trading with the United States at the expense of their previous partnership with Great Britain through Canadian traders. The Hidatsa strongly resisted the American diplomatic efforts, often avoiding meeting with Lewis and Clark.

The Corps spent much time during the winter to prepare for their travel in the spring, repairing equipment, making clothing, processing dried meats, etc. In addition, on the way to their winter site, they had used maps made by previous explorers. From that point on in their westward journey, they would enter territory unfamiliar to Europeans according to known documentation. Clark noted that he gathered information from chief Sheheke about the route to the west in order to make a preliminary map.

Lewis & Clark's Quarters

Not knowing if they would survive the journey, Lewis and Clark used the winter to compile their descriptions of tributaries of the Missouri River, their observations about the Native nations encountered, and their descriptions of plant and mineral specimens which they had collected; all were compiled into a manuscript which they called the Mandan Miscellany. In the spring the captains sent a copy of the manuscript to government officials in St. Louis via their large keelboat. It would return before their expected arrival at the Mandan area in 1806.

Betting on an Indian Princess ! Fort Mandan is where Lewis and Clark met Sacawea. Her husband Toussaint Charbonneau served as a Hidatsa interpreter for the expedition, and the journals imply that she lived at the fort with him. Their son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, whom she kept with her throughout the expedition, was born on February 11, possibly at the fort.

The Voyage of Discovery Troops Quarters.

The very cool dude shared this story on the Fort, while he unlocked the whole fort and gave the Boys a tour every bit as good as if they came before 5:00PM and paid full fare!

After the wonderful gentleman spent 30 minutes in the rain, missing a College Party to chat with two old guys started to lock up again. Bone asked him one more question, "Why was the Fort recreated and moved from the original spot?"

Apparently when the Corps passed back through the area in August 1806 on their return journey to the East, they found the Fort had burnt to the ground. The cause is unknown. Since that time, the Missouri River has slowly eroded the bank and shifted course to the east, putting the former site of the fort underwater, hence they have had to move and rebuild the Fort.

With that he bid adieu to a grateful Mike and Bone.

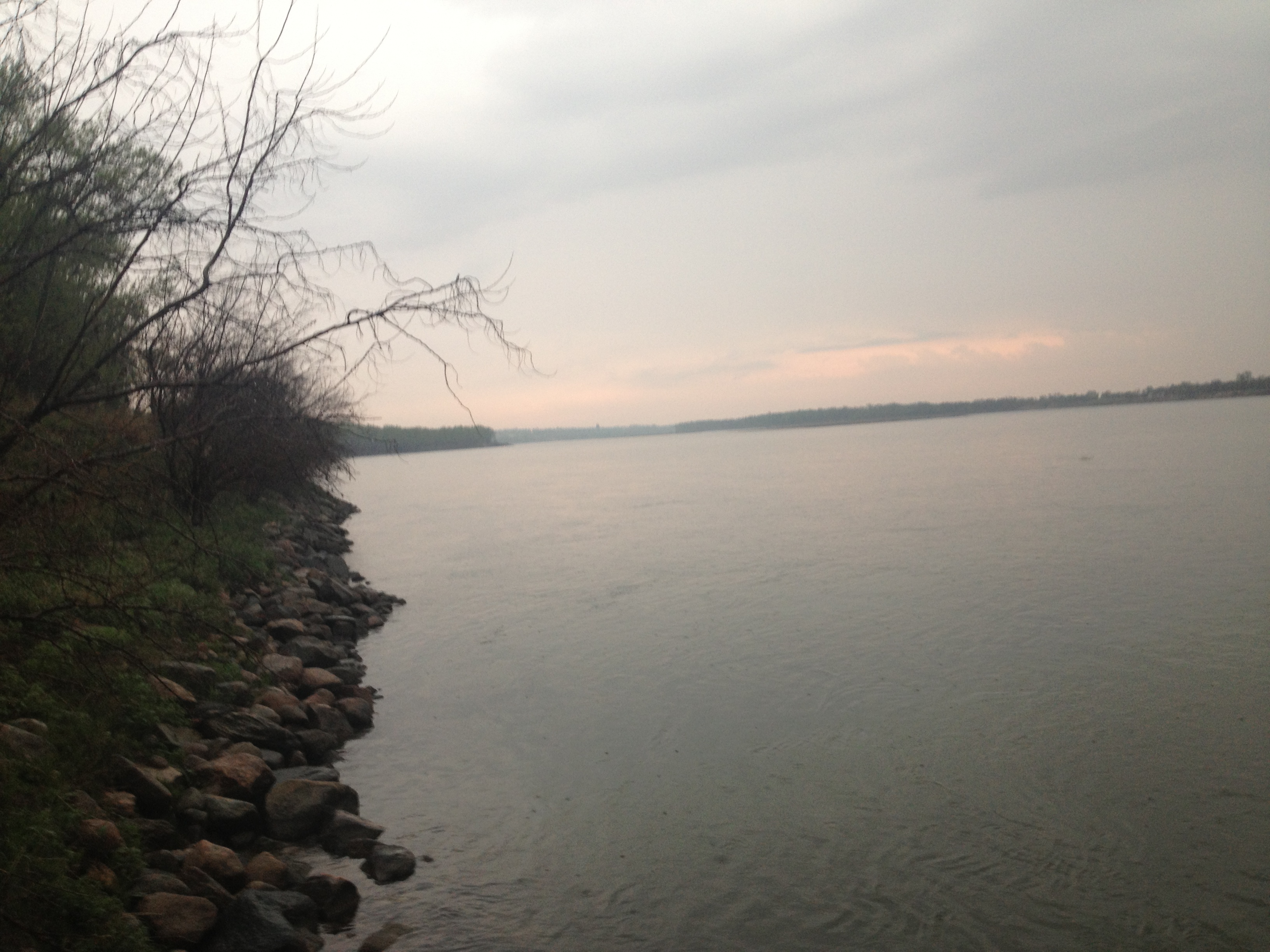

Lewis & Clark's View of the Mighty Missouri

The irony is that the despite thanking him repeatedly the Boys never got his name! With that, they took a couple of photos of what Lewis and Clark saw on the Mighty Missouri and sat exhausted as the rain came down even harder!!

Outta Gas, and Outta Gas !!

The Boys did it! Three sites, two states in one day! Now they needed some gas or the dang car was gonna run out! Luckily, there was a Gas Station within a quarter mile where Mike and Bone filled, and unfilled used hall of shame contents. Now, they had a flight the next morning at 8:00 from Minneapolis which was a good four hours east. Since they had been in car for almost 10 hours, Mike suggested that they get within an hour of Minny and call it a night.

The Ubiquitous Hall of Shame

Fortunately the Boys replenished the Hall of Shame with some delicious Newcastles for the very uninteresting ride from through to Fargo to St, Cloud, the Boys target for the night, that would provide the lubricant for the covnerstion the Boys had about the places they just visited and Bone's upcoming move to Japan.

Yah, You are in Minnysooota!

By 10:00 PM the Boys landed in St. Cloud, grabbed a Hotel and headed for a local bar for a micro-brew and a burger, fortunately there was a great local bar just a 1/2 mile away. Sitting on the stools, Mike and Bone relished their juicy burgers and tasty local nut brown ales, tired by satisfied that they did it! Three Parks in one day!

Trip, Postscript

The next morning Mike and Bone rose early and headed to the Airport with no drama. The Boys parted ways at the Airport, Mike to Grand Rapids, and Bone to Japan!